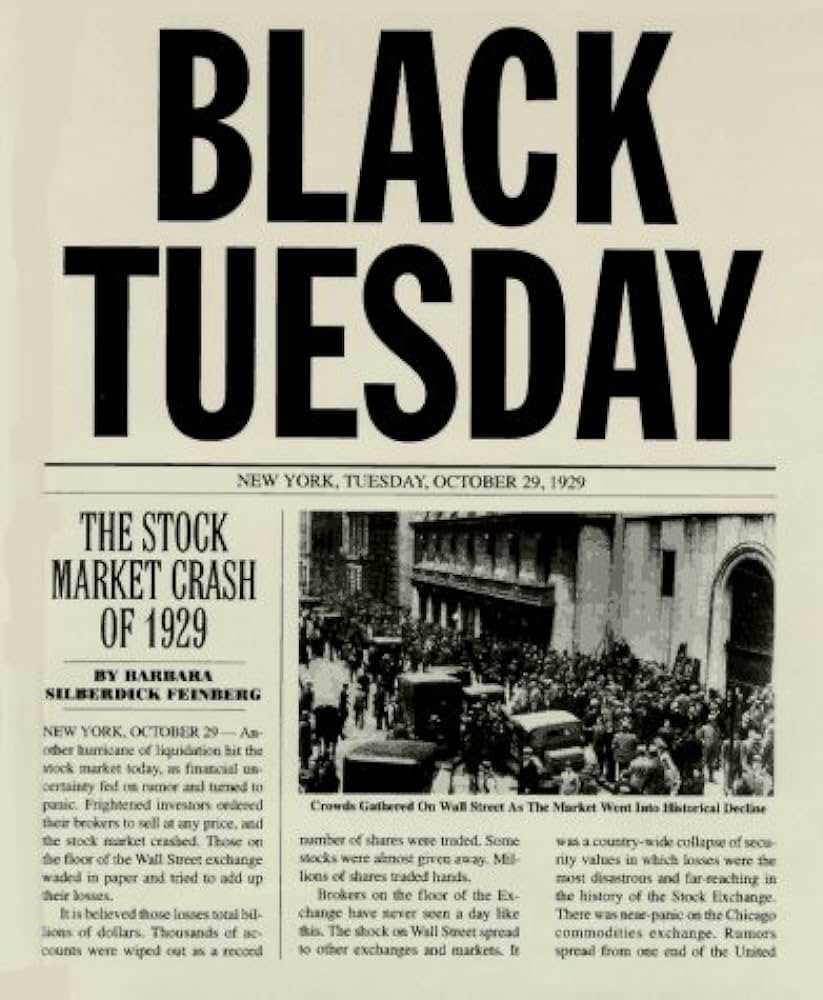

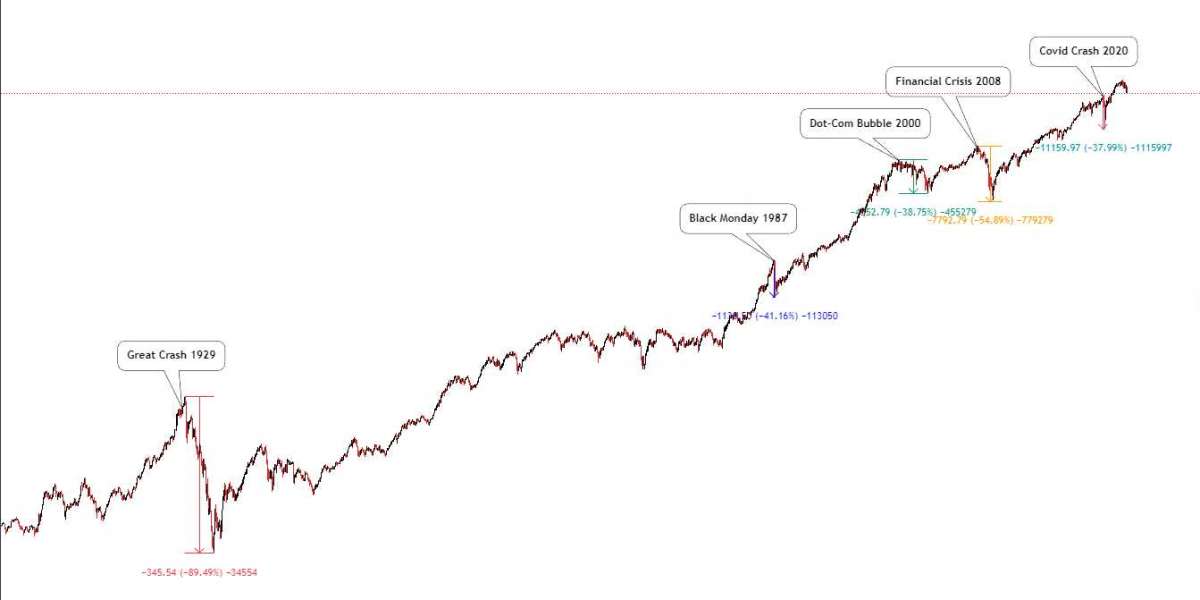

1929 The Great Crash

The collapse of the stock market in the late 1920s was influenced by various factors. Notably, rampant speculation led to substantial losses for investors who had purchased stocks on margin, exacerbating their financial burdens. Additionally, the Federal Reserve's tightening of credit, coupled with the proliferation of holding companies and investment trusts, further strained the market by increasing debt levels. The accumulation of large bank loans that could not be repaid and an ongoing economic recession added to the market's instability.

Throughout the mid- to late 1920s, the U.S. stock market experienced significant growth, famously known as the "Hoover bull market," extending into the early months of President Herbert Hoover's term. Stock prices soared to unprecedented levels, attracting a diverse range of investors eager to capitalize on potential profits. Billions of dollars flowed from banks to Wall Street to finance margin accounts, sustaining the market's upward trajectory

.However, the market's overvaluation became evident in the autumn of 1929, prompting seasoned investors to sell their holdings and secure profits. This initial selling pressure culminated in the crash of October 24, 1929, followed by further declines on "Black Tuesday," October 29, as panic-selling ensued with no buyers in sight. The rapid decline in stock prices precipitated the onset of the Great Depression, a global economic downturn lasting approximately a decade.

Amid the economic turmoil, Franklin D. Roosevelt's presidency marked a pivotal moment with the implementation of the New Deal in 1933. This series of programs aimed to stabilize the economy, provide relief to the unemployed, establish safety net initiatives, and regulate the private sector. While the effectiveness of the New Deal in mitigating the depression remains debated, its legacy extends beyond economic measures, fundamentally reshaping the role of government and introducing enduring social programs integral to American society.

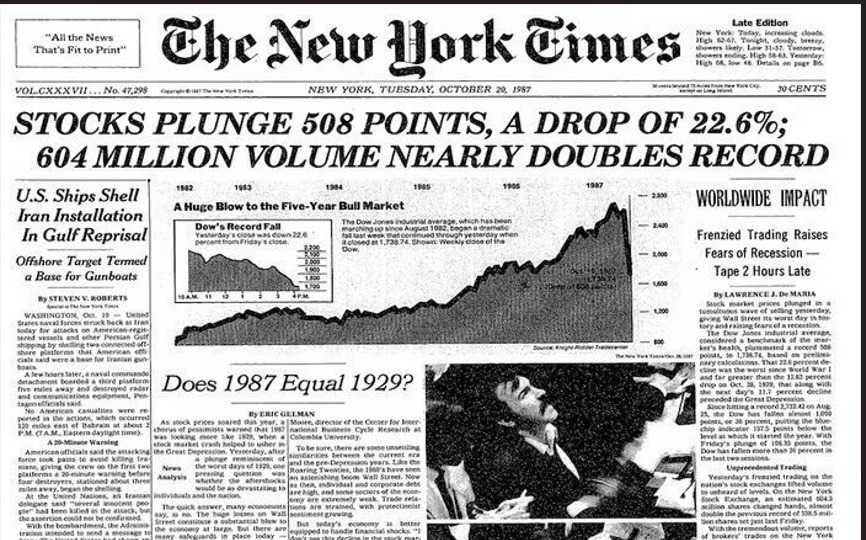

1987 Black Monday

Many market analysts suggest that the Black Monday crash of 1987 was primarily fueled by an extended bull market overdue for a significant correction.

By 1987, the market had enjoyed five years of bullish activity without a major corrective retracement since its commencement in 1982. During this period, stock prices had surged, more than tripling in value over four and a half years, with a notable 44% increase in 1987 alone preceding the crash.

Another factor implicated in the severity of the crash was the emergence of computerized trading, a relatively novel phenomenon in the mid-1980s. This technology empowered brokers to execute larger orders swiftly and efficiently. Additionally, automated software programs were programmed to execute stop-loss orders automatically, selling off positions when stocks declined by a predetermined percentage.

On Black Monday, the proliferation of computerized trading systems exacerbated the pace of selling, intensifying the market's descent and triggering a self-reinforcing cycle of further declines. The cascade of selling set off by initial losses led to subsequent rounds of computer-driven selling, perpetuating the downturn.

A third contributing factor to the crash was the advent of "portfolio insurance," also relatively new at the time. Institutional investors utilized portfolio insurance strategies, partially hedging their stock portfolios by shorting SP 500 futures contracts. These strategies were designed to automatically increase short futures positions in response to significant stock price declines.

On Black Monday, portfolio insurance practices compounded the downward spiral. As stock prices plummeted, institutional investors increased their short futures positions, exerting additional selling pressure on both the stock and futures markets.

In summary, the Black Monday crash was propelled by a combination of factors: an overextended bull market ripe for correction, the advent of computerized trading intensifying selling pressure, and the utilization of portfolio insurance strategies amplifying the market's downward momentum.

2000 Dotcom Bubble

The dotcom crash was ignited by the rapid rise and subsequent decline of technology stocks. The advent of the Internet sparked excitement among investors, prompting a surge of capital into fledgling start-up ventures. These companies, often lacking solid business plans, products, or profitability records, managed to secure huge public funding but quickly depleted their cash reserves, leading to their demise.

The Internet bubble formed due to a confluence of speculative investing, enourmous venture capital for start-ups, and the failure of many dotcoms to generate profits. During the 1990s, investors flooded Internet start-ups with funds, hopeful of eventual profitability. This influx of capital encouraged reckless spending and a disregard for fiscal prudence as companies raced to expand rapidly. Marketing expenditures soared, with some ventures allocating up to 90% of their budgets to advertising in a bid to establish brand dominance.

Beginning in 1997, record levels of capital inundated the Nasdaq, with a staggering 39% of venture capital investments pouring into Internet ventures by 1999. The year 2000 witnessed a flurry of initial public offerings (IPOs), predominantly from Internet-related firms, culminating in the ill-fated AOL Time Warner megamerger in January.

As investment capital dwindled, dotcom companies found themselves starved of resources, leading to a swift collapse. Many companies, once valued in the hundreds of millions, became worthless in a matter of months. By the end of 2001, the majority of publicly traded dotcoms had folded, erasing trillions of dollars in investment capital. Amidst the wreckage, a handful of survivors like Amazon, eBay, and Priceline emerged.

The US government officially marked the onset of the dot-com recession in March 2001. The economic shock following the September 11, 2001 "terrorist" attacks further cemented the demise of the dot-com era, with not a single IPO launched that month—a stark contrast to the exuberance of the preceding years. Thus, the dot-com bubble burst, leaving investors with substantial losses and signaling the end of an era.

2008-2009 Global Financial Crisis

The crisis did not manifest suddenly; rather, it evolved over time due to a multitude of factors, the repercussions of which persist today. At the heart of the global financial crisis was the housing market bubble that began forming in 2007. Banks and lending institutions enticed homeowners with low-interest rates on mortgages, often extending loans beyond their financial means.

In response to the influx of mortgages, lenders devised mortgage-backed securities (MBS), bundles of mortgages sold as securities with purportedly minimal risk due to backing by credit default swaps (CDS). However, lax enforcement of outdated regulations allowed for sloppy underwriting practices, obscuring the true value and stability of these securities.

Reckless lending to individuals and families lacking adequate means led to the aggregation of high-risk (subprime) loans, exacerbating the vulnerability of the financial system. As defaults on subprime mortgages escalated, lending institutions faced mounting financial distress, precipitating a global financial downturn from 2008 to 2009, with enduring ramifications.

The collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 catalyzed a widespread panic in global financial markets, compounded by the near failures of numerous other financial institutions. Subprime mortgage holders defaulted en masse, inflicting significant losses on financial institutions, prompting government interventions to stabilize the banking sector.

The housing market bore the brunt of the crisis, witnessing a surge in evictions and foreclosures, while the stock market plummeted and businesses worldwide faltered, resulting in extensive job losses and prolonged unemployment on a global scale. Declining credit availability and waning confidence stifled investment and precipitated a slowdown in international trade.

In response, the United States enacted the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, employing expansionary monetary policies, facilitating bank bailouts and mergers, and implementing measures to stimulate economic growth. Despite these efforts, the aftermath of the crisis continues to reverberate, underscoring the enduring impact of the events that unfolded during that period.

2020 Covid Crash

The 2020 market downturn stemmed primarily from concerns surrounding the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. The uncertainty regarding the virus's impact, combined with widespread government-mandated business closures, inflicted significant damage across various economic sectors. Projections of extensive job losses and decreased consumer spending heightened investor apprehensions, leading to a swift decline in global markets, including the Dow Jones.

The World Health Organization's declaration of the pandemic on March 11 exacerbated investor anxiety, underscoring concerns about inadequate government responses to curb the virus's rapid spread. Additionally, ongoing worries stemming from President Donald Trump's trade disputes with China and other nations contributed to market instability.

In response to the economic fallout, both the Trump and Biden administrations implemented a range of stimulus measures to support the economy. These initiatives included targeted assistance for specific sectors, direct financial aid for individuals, enhanced unemployment benefits, and rental relief. These interventions helped alleviate some investor concerns, contributing to market recoveries.

Moreover, optimism surrounding the development and deployment of COVID-19 vaccines, initiated during the Trump administration, further bolstered investor confidence. Despite the unprecedented challenges that precipitated the 2020 market downturn, sustained belief in the market was reinforced by a combination of government support and progress in vaccine development.

Wes Soleiman 39 w

Well I just got a whole lot of education. Amazing write up.